Universities can help lead the way through the era of “creative destruction” of journalism. But only if they are willing to destroy and recreate themselves.

The Carnegie-Knight Initiative on the Future of Journalism Education demonstrated that change is possible. Change at the participating schools went far beyond what the foundations funded: digital-first curriculum; deep subject knowledge; collaboration and innovation; high-impact student journalism in major media, and graduates going straight into major media roles.

The Carnegie-Knight Initiative on the Future of Journalism Education demonstrated that change is possible. Change at the participating schools went far beyond what the foundations funded: digital-first curriculum; deep subject knowledge; collaboration and innovation; high-impact student journalism in major media, and graduates going straight into major media roles.

We did not buy those changes. Twenty million dollars seems a substantial sum. But there were a dozen schools involved over many years. In reality, our grants represented only a fraction of a percentage point of the budgets of these schools. The grants were a catalyst. We brought hope and a helping hand. The schools did the rest.

The initiative revealed four transformational trends in journalism and mass communication education, discussed below. The best schools already are living these trends. Some educators do not accept them. They argue that budgets, presidents, provosts, faculty, students, the rules — “the system” — are roadblocks to change.

So that leaves two choices: either the system really does block change, or all of that is just an excuse. If the system is blocking things, I will suggest some ways to blow it up. But if the system is not the problem, educators should help one another by sharing road maps to reform.

So that leaves two choices: either the system really does block change, or all of that is just an excuse. If the system is blocking things, I will suggest some ways to blow it up. But if the system is not the problem, educators should help one another by sharing road maps to reform.

If colleges and universities want to ride the four transformational trends demonstrated by the fastest-moving schools, here’s what they need to do to be relevant in the future:

1. Expand their role as community content providers. Just as university hospitals save lives and university law clinics take cases to the Supreme Court, university news labs can report stories that help right wrongs. Based on the teaching hospital model, they can provide both the news and the civic engagement people need to run their communities and their lives.

2. Innovate. Journalism schools can create both new uses for software and new software itself. Anyone can create the future of news and information. Anyone includes us.

3. Teach open, collaborative methods. No longer should students be lone-wolf reporters or cogs in a company wheel. In small, integrated teams of designers, entrepreneurs, programmers and journalists, students can learn to rapidly create prototypes of news projects and ideas.

4. Connect to the whole university. This can mean scientists helping teach science journalism classes … or the creation of “knowledge journalism” … or innovation centers with engineers or entrepreneurs … or research on local news experiments. Journalism need not abandon “the university tradition.”

University presidents had to pay for some of this reform themselves to be part of Carnegie-Knight. Their view of journalism and communication changed. They saw the value of their schools to the wider community.

Top professionals have a critical role

Beneath these trends lie challenges and opportunities. Probably the most important one: top news professionals are as central to the task at hand as top scholars. You can’t run a teaching hospital without doctors (you shouldn’t run one with without researchers, either). Professionals and professors will need to work together in ways most have not.

Curriculum reform needs to be more than dissolving print and broadcast silos. It should redefine journalism as an intellectual activity in its own right. Call it the art of critical inquiry and real-time high-impact, community-engaged exposition and analysis. If you teach journalism merely as a skill, it becomes nothing more than a skill. Teach journalism as the most exciting profession of this century, and it becomes that.

Having been part of more than $100 million in grants to universities, I would like to offer an observation: top scholars, top journalists and top schools welcome change. Mediocre schools do not. At the top, great minds think alike. The resistance comes from the middle.

Many have championed journalism and communication school reform. A diverse, bipartisan, independent Knight Commission called for “fresh thinking and aggressive action” to deal with the digital age. The FCC’s “Information Needs of Communities” declared a crisis in local accountability journalism and asked universities to step up. A report by the New America Foundation detailed university content efforts and called for more.

With all due respect, journalism and communication education plays second chair, and sometimes first chair, in a symphony of slowness. Consider: on one side of campus, engineers have been inventing the Internet, browsers and search engines. But the news industry is slow to respond. Public radio slower still. Foundations even slower. Government slower yet again. Then come the journalism and communication schools, just across campus from the engineers who started it all. And finally, local public television stations.

Who suffers? Students, to say nothing of society as a whole. As social and mobile media were taking off, a survey showed that almost half the nation’s journalism and communication school grads were not sure the field was “very different” from the way it was five years earlier. This, when in fact there were record news company bankruptcies, layoffs, congressional hearings, new media empires as well as an explosion in new journalism techniques. Yet half the graduates were not sure communications work was very different. Who, you have to wonder, is teaching them?

Certainly not digitally savvy professors like Amy Schmitz Weiss and Cindy Royal, who advocate journalism education reform and teach current technology. They are among the educators who are members of the Online News Association. Yet that group’s Facebook page in fall 2013 listed only 425 teachers when college-level journalism and communication faculty number more than 12,000. Perhaps that explains why college student media took 20 years to get onto the World Wide Web. Do the students who are unsure that change is happening get that idea from professors who also are unsure?

Society in general suffers as well. News and information is a core social need, as crucial to healthy communities as safe streets, good schools and clean air. As veteran editors like the late John Seigenthaler have reminded us for generations, journalism is an essential ingredient of democracy. To that end, and because of the local news drought, foundations are stepping up their investment in news and information projects. Journalism educators could join in. Put simply, the social and mobile era offers a do-over moment for journalism education.

My wish list for what should be done is meant to provoke. Following Jack Knight’s model for a good newspaper, I hope to help educators become aware of their condition, inspire thought and rouse them to pursue their true interests.

First, journalism schools should live up to the new standards enacted by the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, particularly the new flexibility in curriculum allowing students to learn more business and technology. That said, I also hope students can continue to take even more and better core journalism classes. Journalism, the nonfiction profession, should be learned by all communication students. This is even more important now because new technology allows everyone to act as a journalist.

Some of us pushed hard for

(As an aside, when I came to the Knight Foundation in 2001, we had an internal rule that only accredited schools could be considered for grants. That rule lasted about a week. A professor called. I asked: Are you accredited? “Yes.” Do you have a website? “No.” But it’s been seven years since the World Wide Web hit. You must have had an accreditation visit. “Yes.” And no one cared that you didn’t have a website? “No.” Do you know it only takes a few minutes to create a website? “It does?”

At that moment, I thought there should be a new rule: never mind accreditation. A better rule: If the most profound change in human communication in half a millennium comes along, and you are not doing anything about it, you can’t apply for a grant. Today, that means a lot more than having a website. It means having a good website. It means embracing social and mobile media. It means not waiting a decade to respond to whatever comes next.)

At that moment, I thought there should be a new rule: never mind accreditation. A better rule: If the most profound change in human communication in half a millennium comes along, and you are not doing anything about it, you can’t apply for a grant. Today, that means a lot more than having a website. It means having a good website. It means embracing social and mobile media. It means not waiting a decade to respond to whatever comes next.)

Another new accreditation requirement calls for schools to post on the web their retention and graduation rates. That’s a start, but great schools should reveal even more. After all, they are communication schools. They should design systems that allow open, real-time reporting. Accreditation self-studies, staff technology expertise, even down to software taught or created, should appear on a school’s website. The percentage of graduates who get jobs in their field should appear at the top of the home page, with an explanation if that number is zero.

The ACEJMC diversity standard still needs expanding. It should consider all the social fault lines — gender, race, generation, geography, class and ideology. These fault lines may be relatively equal in impact, but on campus, the gender gap is the biggest. Look at how many students are women, more than 60 percent and growing. Look at how many deans are women. Is it 30 percent? Lower? Why is that number so hard to find?

Hiring and retaining top professionals

Several recommendations on my wish list have to do with the growing need for top journalism professionals in the academy. We need to include exceptional news professionals in the most respected ranks of academia, the way medical schools appreciate doctors and law schools respect lawyers. The $60 million Knight Chair program, at more than 20 universities, proves this can be done. Many of these chairs are national leaders. They are chosen for their genius, not their degrees. A degree is a surrogate measure of talent, and sometimes, not a very good one.

To some institutions, our professional chairs (nearly all of whom have tenure) would be unacceptable. I refer now to the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, the regional accreditation group with which I am most familiar. SACS is an appropriate name for a group blamed for sacking the professionals in academia.

Consider the SACS standards for hiring faculty. A university should give “primary consideration to the highest earned degree in the discipline,” the standards say. After that, “the institution also considers competence…” Also? According to SACS, the degree is primary, competence is an also-ran.

The SACS rules allow a school to argue for “unusual” or “exceptional” people. All one needs to do to defend worthy professionals without advanced degrees is provide a simple written explanation. Unfortunately, more than a few deans, provosts and presidents seem to think that is simply too much trouble. I’m sure there are stories to be told about the great professionals who were retained by virtue of cogent explanation. But we don’t hear them. We hear instead of faculty who have been unjustly demoted or fired. Sometimes, these people are so exceptional that Knight or another funder has given them a grant. Imagine our surprise when they are dismissed. Even though they are top professionals with extraordinary competence, singled out for their excellence by national foundations, they have been abandoned by their deans, provosts and presidents. The administrators say it isn’t their fault, that everyone should blame SACS; SACS says it isn’t their fault, the administrators are the ones who either defend staff or don’t.

Great professionals and great scholars are equal. They both make important contributions. But in academia they are not equal. Tenured professors have lifetime job guarantees; professionals often are hired on a class by class basis. Professors determine curriculum and sit on hiring committees. The “adjuncts” — professionals brought in to teach things faculty don’t know, often at near minimum-wage — don’t have a say in a school’s direction.

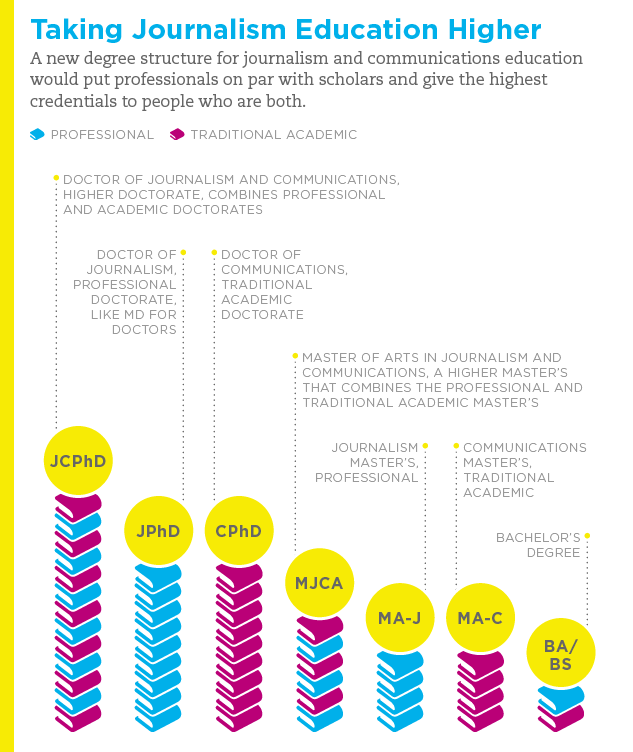

We can begin to address the inequities between top professionals and scholars by establishing a new degree structure that creates a professional PhD in journalism, just as there is a JD in law and an MD in medicine. Until then, we should recognize that “highest earned degree in the discipline,” for a professional, is a master’s. The City University of New York does it. Until there is a professional doctorate, all programs should consider the master’s a terminal degree for professionals.

We should push for all good schools to have a higher master’s — call it an MJCA — a Master of Arts in Journalism and Communications. Just as there are MFAs and MBAs, there should be a higher master’s degree for journalism. It would combine theory and practice, research and impact. Every thesis should be readable as measured by its Flesch score. Every thesis should be free and online. Before an MJCA degree is awarded, the candidate should attract significant attention to (and engagement with) his or her thesis.

We also need a professional doctorate. Call it a JPhD, a Doctor of Journalism and Communication, just as there is an MD, a doctor of medicine. To earn that degree you would need to demonstrate journalism excellence; innovation that creates new techniques, technologies, story forms or pioneering content; and, most importantly, your intellectual contribution should show community impact.

Some professionals could qualify for this type of degree in less time than it would take to get a scholarly PhD. They have spent decades in the field developing doctoral-level knowledge. But they would still need to learn how to put that work in scholarly context, show what theories it supports or debunks.

And finally, we need what the British have: a higher doctorate. This would be a JCPhD, superior to all other degrees in the discipline, a super degree. You would need to do everything the doctor of journalism and communication can do, plus everything a traditional academic PhD — call it a CPhD — can do.

And finally, we need what the British have: a higher doctorate. This would be a JCPhD, superior to all other degrees in the discipline, a super degree. You would need to do everything the doctor of journalism and communication can do, plus everything a traditional academic PhD — call it a CPhD — can do.

The higher doctorate as well as the higher master’s grant special status to renaissance people who can be both professionals and scholars. A university pioneering this idea will need courage, because all of its current PhD holders may suddenly think they have only a penultimate degree, not the so-called “terminal degree”.

Much work remains to achieve equality between top professionals and top academics. I’m reminded of the Oregon report of 25 years ago, calling for a mix of scholars and professionals, and then “Winds of Change” 15 years ago, seeing not a coming together but a widening rift. Most notable was how so many scholars used words like “vocational,” “training” and “skill” to describe journalism, and words like “intellectual,” “scholarly,” and “peer-reviewed” to describe their work.

I wonder if scholars understand how dismissive this is. How would they feel if their chosen field was described that way? Let me try: Research without real accountability is a vocational pastime, a narrow skill applied to a limited number of jobs. Thusly seen, advanced study is an occupational degree: It qualifies you to teach and write papers, and that’s it. People who are interested in real intellectual challenges avoid PhD training.

I do not claim that the above is at all true. My intention is to show how it feels to have an intellectually rigorous endeavor — as journalism is, at the highest levels — described essentially as work for dummies. I do claim the following is true: The professor-professional gulf damages journalism education. It has become the mark of a mediocre institution when it can’t distinguish between top professionals and average ones, just as it is the mark of a mediocre newsroom when it can’t tell the difference between a good scholar and an average one.

Joining research and innovation

United, the clans will discover many opportunities for collaboration. For the first time, a serious number of journalism and communication schools are experimenting. Who will study these experiments? Who will address the social science of engagement and impact? The answers will arise when we can get scholars and professionals to work together.

To be fair, the door should swing both ways. Newsrooms should embrace leading journalism scholars, twinning them with the best professionals in efforts to understand the digital world. Columbia University did just that when it placed editor Len Downie with scholar Michael Schudson to write the report, “The Reconstruction of American Journalism.”

There’s plenty to study. The “teaching hospital” model, not as it is generally practiced but as it should be, needs to produce newsrooms that more deeply understand and engage the communities they serve. In this interactive world, we need to know why some stories are debated, shared and acted upon while others aren’t. These are research topics best pursued in the living laboratory that is a working community news system.

On the positive side, some schools are adapting. They are trying new degrees and graduate degrees, new story forms; teaching data journalism, web scraping and computational journalism; developing entrepreneurial journalism programs and new software (including games), and even opening a center for drone journalism. Some are experimenting with new tools as fast as they come out. Those schools are teaching numeracy as well as literacy. They will produce better students.

Some are comfortable with “reverse mentoring,” where smart students teach professors about cutting-edge digital issues and professors teach students traditional journalism values, the fair, accurate, contextual search for truth.

Arizona State University is a good example of a school taking on the four transformational trends. Faculty there are helping students provide digital news in new, engaging ways. They are innovating content and technology. They are learning to teach open, collaborative models, and they’re connecting with the whole university. They have not abandoned quality journalism; they’ve enhanced it.

But there could be even more change. Why not teach the 21st century literacies — news literacy, digital media fluency, civics literacy — to the entire campus? If you have the right budgeting system, an influx of many thousands of students from other departments into yours can bring more money. At Stony Brook in New York, they are teaching news literacy to 10,000 students. At Queens University in North Carolina, they are teaching digital and media literacy to the entire community.

Money for these improvements can’t be found unless it is sought. Community foundations can play a role. For years, Knight Foundation has run the Knight Community Information Challenge, encouraging more journalism and media grant making by matching community foundations that funded local projects. But few community foundations looked to their local journalism schools for a helping hand. The Knight News Challenge looks for projects that combine news, innovation and community. It tends to hear from a small number of schools. Similarly, the Department of Education money for tech experiments and the broadband expansion and adoption money has not gone to journalism and communication schools, with a few exceptions, such as Michigan State. Schools might try harder to get some of those federal funds.

Once the economy recovers, we’ll be ripe for new federal program ideas. How about brainstorming something like a Media Corps, where students would get full scholarships for staying on after graduation to provide community content and help their schools transform?

Once the economy recovers, we’ll be ripe for new federal program ideas. How about brainstorming something like a Media Corps, where students would get full scholarships for staying on after graduation to provide community content and help their schools transform?

Our government is doing this for the military — giving students free computer science degrees if they will serve the nation as cyber soldiers. Perhaps deans could organize and propose that the nation care for the communication of peace as it does for war.

We live in a paradoxical age. My concerns are mixed with excitement. All things considered, we should delight in the privilege of being alive at this turning point in history. Certainly, the students are enthusiastic. They continue to come in record numbers, ready to teach as well as learn, to find the new jobs wherever they are created. Journalism and communication schools find themselves offering the great all-purpose degree of the 21st century. What more can be done with that?

Pioneering publisher Bob Maynard used to say that all things worth doing begin with someone who passionately believes in them, even when others say they are not possible. He thought the moribund Oakland Tribune could become a Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper, and it did. Al Neuharth believed The Freedom Forum could create an engaging, high-tech museum of news, and now we have the Newseum. Alberto Ibargüen believed Knight Foundation could help journalism by experimenting with media innovation, and hundreds of newsrooms are using tools developed with Knight funding.

Engaging the possible requires leadership. Even if you don’t want to blow up the systems as I’ve proposed, if you passionately want reform, it will happen. To get there, you first have to get past the most difficult barrier of all, the voice in your heads that says it just can’t be done.

Transformational trends in journalism and mass communication education are beginning, despite underlying structures. That’s because people like you have decided it’s going to happen, no matter what. Blow up the rulebook if you need to. If not, please come up with better ideas. The future depends on it.

This is adapted from a speech delivered to a national conference of journalism educators at Middle Tennessee State University.

- OFF

- ON

-

Evolution or revolution?

-

Carnegie-Knight: Journalism schools can innovate

-

Journalism education reform: How far should it go?

-

Journalism funders call for ‘teaching hospital’ model

-

Why journalism funders

like ‘teaching hospitals’ -

The promise and peril of teaching hospitals

-

A problem with academic research into journalism?

-

Demand Grows for Digital Training

Learning layer directory

Learning layer directory