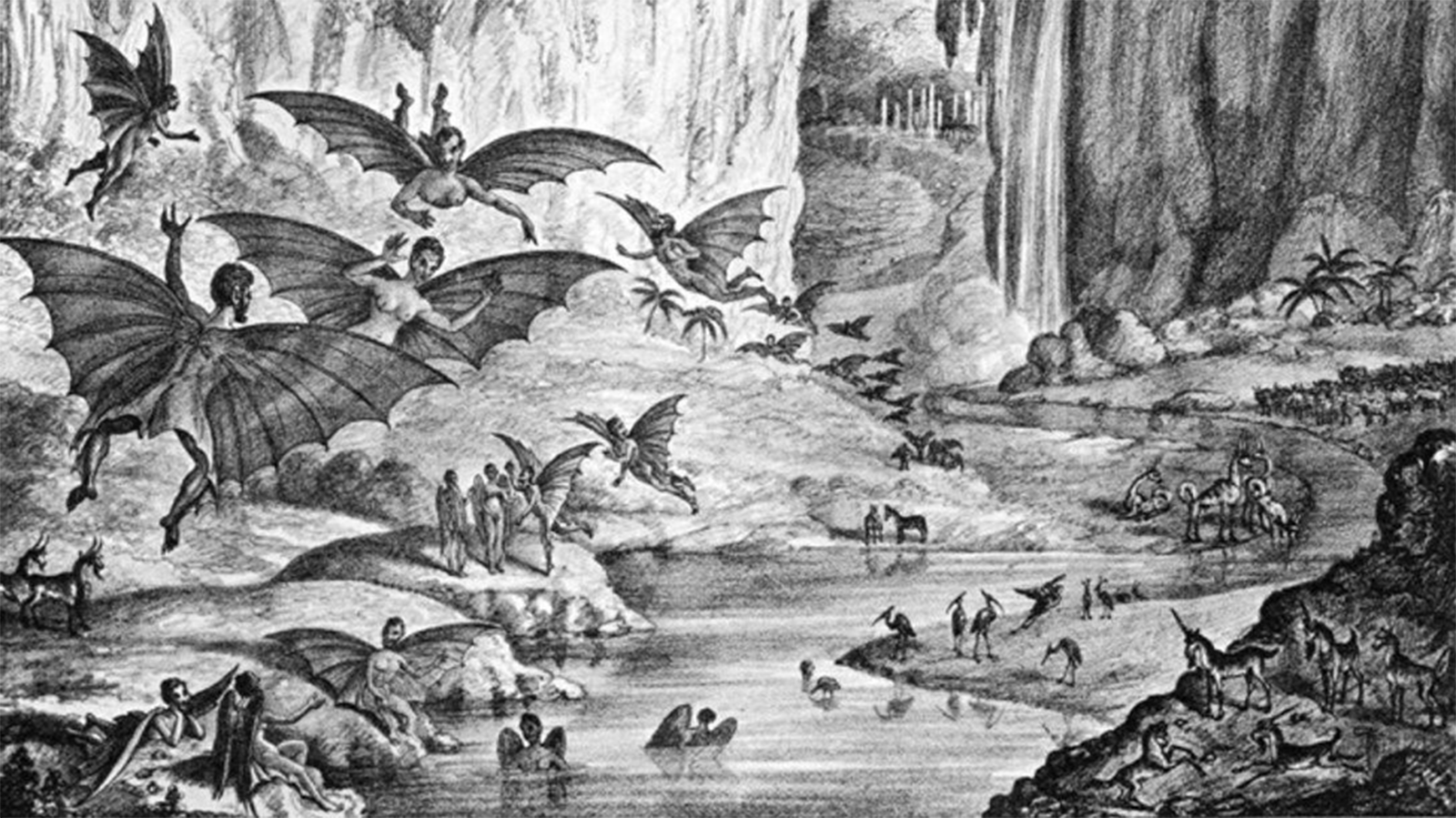

Addressing the centuries-old problem of fake news requires innovative approaches. Technologists, journalists, educators, researchers and others have a role. Everything from “correction bots” to greater journalism transparency to a high school “news literacy” requirement was discussed recently at a “news literacy working group” meeting co-hosted by Facebook and the Cronkite School. Cronkite School Innovation Chief Eric Newton reported on the issue and some of the ideas. Illustration: The “bat people” discovered living on the moon, according to a series of stories in the New York Sun in August 1835. Public domain image.

By Eric Newton

Jonathan Swift once wrote: “Falsehood flies, and truth comes limping after it.”

Today, thanks to the internet, search engines and social media, falsehoods fly around the world at the speed of light. And as they go, they leave fact far behind.

This is a perilous situation indeed, since the first step to solving common problems is finding a common set of facts. A profound question in the media world — and in the world — today: How or where do we find that common set of facts in light of the onslaught of flying falsehoods?

In March, I took part in a “news literacy working group” here at the Cronkite School at Arizona State University, to gather innovative ideas on how to help the public distinguish falsehood from fact, the phony news story from the real one. Advancing news literacy is an urgent undertaking amid the current epidemic of so-called “fake news.”

The working group, co-hosted by ASU and Facebook, agreed to use the Chatham House Rule. That means each member is free to say that he or she was at the meeting, but no one can disclose who else was there, or who said what.

First, for clarity’s sake: As I see it, “fake news” is news that is designed to mislead. It is specious. A fraud. A sham. A con. Fake-news web sites know the stories they create are false. They spread hoaxes by crafting them to resemble actual news stories.

These “stories” succeed only to the extent that they deceive. The Web site creators often do all this to make money and/or wield political influence.

Sloppy journalism is not fake news. All journalists make occasional mistakes, but there is no intent to deceive.

As a lifelong news professional, my own starting point on the power of news literacy can be found in something my wife and I wrote years ago:

“Always there have been those who would control news and those who would free it; those who use news to mislead and those who use it to enlighten.”

Indeed, fake news is not new. In 1835, to cite a famous example, one of the first populist American dailies, the New York Sun, printed a series of stories hailing the discovery of life on the moon.

Lest anyone doubt the spectacular find, the newspaper printed a drawing depicting moon creatures as seen through an amazing new telescope. They looked a bit like us, but with huge bat-like wings, and they frolicked along riverbeds with unicorns and other strange beasts.

The series created much public excitement. Briefly, that is, until the newspaper revealed it to be an entertaining hoax, and then congratulated itself for having duped everyone.

These days, our media landscape is awash with the modern-day equivalent of bat-winged moon creatures.

But I do not think the answer to false information is trying to eradicate it, an act that has proven impossible in free societies.

What, then, are the answers? Scores of ideas were advanced at the working group. Some of my favorites:

Technology

Technology companies could develop ways for people to more easily access, use and correct the personal information that businesses large and small have on each of us. They could allow more individual control over news feeds, more ways to pop one’s “filter bubble.” Platforms might create ways for high-quality news to circulate more widely. Technologists might develop “correction bots,” so that any future corrections on articles you like or share are called to your and others’ attention.

Journalism

News organizations, from the tiniest news Web site to the largest national media company, could commit to making their journalism more accurate and transparent. They should be engaged in constant conversation with their communities about how they are doing, what is expected of them and how that community might help.

Public awareness

“Fake news” opened the door to greater public awareness about news literacy. Media, community, local government and non-profit groups could work together to find ways to expand that awareness. Prize-winning journalists could serve as public ambassadors of news. Ad campaigns, reality-TV shows, game shows, games, movies — any might work. We could come up with new names, such as the Internet News Workshop. The message: News literacy can be fun.

Research

Academic researchers can focus on solving specific problems. There is much we don’t know conclusively: How fake news flows; why people believe what they believe; why some corrections and fact-checking systems seem to work and others don’t, and which forms of news, media, civic and digital literacy learning work best in the classroom or cyber-classrooms. Both platforms and news organizations could find ways to open their data sets to these researchers.

Education

We need to develop an audacious goal of instilling universal new literacies for the young, one shared by news and technology companies. Schools need to be able to adapt more quickly to change, and states need to pass new laws requiring civic, media, news and other literacies. At the same time, we must use digital tools and online classes to help people learn news literacy beyond the classroom, in social media, in libraries, at civic groups, or in boys’ and girls’ organizations.

These varied approaches — tools to help find credible news; journalism transparency; public awareness projects; better education, and knowing how people and news interact — have one thing in common.

They are ideas of creation. They add to the world’s supply of good information. Just as established fact-checkers (such as Snopes and factcheck.org) already do.

My ASU colleague Dan Gillmor, in his book “Mediactive,” argues convincingly that news consumers themselves need to continue upgrading in sophistication just as media and technology do.

Gillmor, who posted his thoughts on the Facebook-ASU working group, represents a bright spot. He teaches two online media and news literacy courses and has taught a MOOC (a massively open online class), with the materials published under a Creative Commons license, so they can be used and remixed by anyone.

Promising work is taking place elsewhere. The News Literacy Project has a virtual classroom called Checkology. The Center for News Literacy has a free online class. First Draft coalition has social media verification tools, the Duke Reporters’ Lab’s, fact-checking tools; the Poynter Institute, an international fact-checking group, and the Trust Project, transparency tools for media.

This is just a handful of examples of innovative work already taking place. But it is still a beginning. Which of these ideas and projects will Facebook, Amazon, Google and the rest of the techno-world embrace? Which will news companies, foundations or governments support? Things are starting to move, but we don’t yet have the full picture.

In a way, those questions miss the point. News literacy is not a problem of any one domain or entity. The bigger question: Will many groups — The Facebook Journalism Project, Google News and News Lab, Knight Foundation, technologists, journalists, educators, librarians — all get more involved in news literacy?

The fact that technology has always spread faster than human understanding of how to use it makes this everyone’s problem.

Consider books. They existed for centuries before basic literacy – the ability to read and write — became the global norm. (Even today, though, at least 14 percent of the world can’t read.)

Twenty-first century literacies are a bigger challenge. Only a major, extended effort will meet them, and only if we use the power of digital technology for self-teaching tech platforms, journalism, and distance learning.

It’s addition, not subtraction. We need to add news literacy education to the news stream, not think we can easily solve this by trying to subtract fake news.

Human progress these past 500 years has not occurred because of an absence of malice, but because of the presence of freedom.

(Author’s notes: I’ve been involved in news literacy nearly my entire career, at the Oakland Tribune, a “teaching newspaper”; at the Newseum, the museum of news, and at Knight Foundation, developing news literacy grants. And finally: When I use the term “news literacy,” I mean it as a critical part of the larger field of media literacy. I’ve learned a great deal, and continue to learn from digital and media literacy scholars such as Renee Hobbs and organizations such as the National Association for Media Literacy Education. Follow me on Twitter, @EricNewton1.)

Learning layer directory

Learning layer directory